Hjärnstorm, the Swedish independent journal of art, literature, philosophy published an article on Deep Space.

Publication Valle de los Caídos: the Digital Architecture Embraces a Painful Heritage, Cecilia Nyman @ Hjärnstorm Stockholm, 5 January 2021

Valle de los Caídos:

Digital Architecture Embraces a Painful Heritage

In October 2019, in European media one could see pictures of a group of men in costumes shrugging a heavily decorated coffin. The scene featured relatives of Francisco Franco, who during a private ceremony transported the remains of the Spanish dictator out of the Valle de los Caídos. A film clip shows the coffin being lifted into a helicopter that takes off and flies away beyond the 150 meter-high cross that rises high above one of Europe’s most visited memorial sites.

Valle de los Caídos is a huge memorial park outside Madrid that was built after the personal order of Francisco Franco and was completed in 1958. The facility, which is partly located on a cliff, covers just over ten square kilometers and houses one of the world’s largest basilicas. Franco’s gravesite was located in the heart of the facility. José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of one of the phalangist parties that together made up the fascist regime in the 1930s, is buried in the same place.

It was after the Civil War – caused by the nationalists’ revolt against the ruling Republicans – that Francisco Franco in 1939 became a dictator in Spain. During the Civil War, both sides had committed war crimes, but Franco’s regime became known as one of the most violent in European history. It has been estimated that 100,000 people were executed by the regime in fascist Spain. Hundreds of thousands of innocent people were thrown into prison and half a million were driven into exile. Persecution and murder became the tools that allowed the fascists to retain power until Franco’s death in 1975.

Only a few years after Franco’s death, the first free referendum was held in Spain. The outside world was amazed at how quickly the country returned to democracy, but critics have pointed out how the rapid transition took place at the expense of the Spaniards’ right to redress for the crimes committed during the war and the dictatorship. On the contrary, people from Franco’s leadership were allowed to continue working in the right-wing Conservative Party, Partido Popular. And no lawsuits and investigations to establish war crimes and abuses were ever seen.

The Social Democratic Partido Socialista Obrero Espanol, who, together with the Partido Popular, has switched to power after the transition to democracy in the 1970s, proposed a new law with the aim of compensating for the non-management of the Francoist legacy. In 2007, the “Law on the Historical Memory” was enacted, where the promise to move Franco’s remains from the Valle de los Caidos was one of the measures.

But there is concern about the handling of the Valle de los Caídos even though Franco’s grave is now empty. Another part of the law of remembrance concerns the excavation of graves other than those of the dictator. Many of those who disappeared during the war and the dictatorship have never been found and relatives still lack a memorial site for their dead. But many of the remains of the victims have not in fact disappeared but are, as the name reveals, in the Valley of the Fallen. About 34,000 people, most of them unidentified, are buried in a crypt at the basilica that pays homage to Francisco Franco. And the fact that soldiers and prisoners of war who were murdered by the Franco regime are still buried under the monument that pays homage to the dictator is controversial. The Social Democratic government has thus begun the search for remains to enable relatives’ desire to bury them elsewhere. Even though the work is underway, things are slow, partly due to the fact that the conservative party Partido Popular, which has a much more distanced attitude to the law, regained government power in 2011.

The inertia has not only been due to the reluctance of Partido Popular to support the law but also due to the spatial conditions in place. In the newspaper Archinect (2018), a Spanish journalist reports based on some government documents that confirm suspicions about the poor condition of the crypts. Walls and ceilings have imploded with leaks, which means that the materials are no longer intact. In some cases, the condition is reported to be so bad that the remains and walls are inseparable. The bones have become one with the building. This means that despite a politically powerful situation, it will be difficult to return remnants, even if the law promises it.

Hybrid Space Lab proposes a digital architecture as a tool to think carefully about the past and to make memorial sites an arena for the fallen rather than for the dictators.

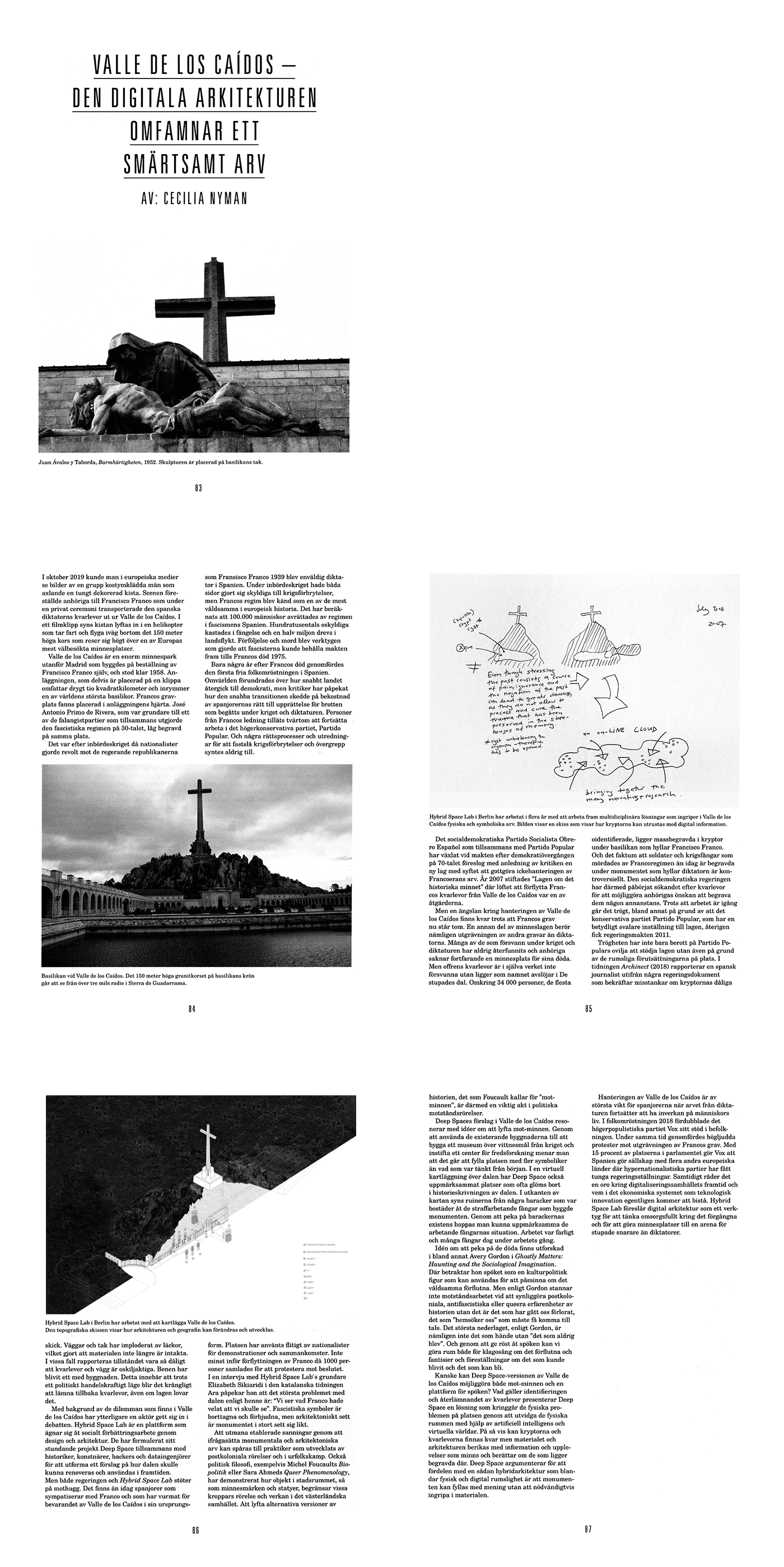

In view of the dilemmas that exist in the Valle de los Caídos, another actor has entered the debate. Hybrid Space Lab is a platform that is committed to socially engaged work through design and architecture. They have formulated their upcoming project Deep Space together with historians, artists, hackers, and computer engineers to design a proposal on how the Valley could be transformed and used in the future. But both the government and the Hybrid Space Lab are facing setbacks. There are still Spaniards who sympathize with Franco and who have been crazy about the preservation of the Valle de los Caídos in its original form. The site has been used extensively by nationalists for demonstrations and gatherings. Not least before the transfer of Franco when 1000 people gathered to protest the decision. In an interview with Hybrid Space Lab’s founder Elizabeth Sikiaridi in the Catalan newspaper ARA, she points out that the biggest problem with the valley according to her is: “We see what Franco wanted us to see”. Fascist symbols have been removed and banned, but architecturally the monument is largely the same.

Challenging established truths by questioning monumental and architectural heritage can be traced to practices developed by postcolonial movements and in the indigenous struggle. Political philosophy, such as Michel Foucault‘s Biopolitics or Sara Ahmed‘s Queer Phenomenology, has also demonstrated how objects in urban space, such as monuments and statues, restrict the movement and limit the impact of certain bodies in Western society. To lift alternative versions of history, what Foucault calls “counter-memories”, is thus an important act in political resistance movements.

Deep Space’s proposals in the Valle de los Caídos resonate with ideas of raising counter-memories. By using the existing buildings to build a museum of testimonies from the war and establish a center for peace research, it is believed that it is possible to fill the place with more symbolism than was originally intended. In a virtual survey of the Valley, Deep Space has also drawn attention to places that are often forgotten in the history writing of the Valley. At the edge of the map, the ruins of some barracks can be seen, which were housing for the prisoners of war who built the monument. By pointing to the existence of the barracks, one hopes to be able to draw attention to the situation of the working prisoners. The work was dangerous and many prisoners died during the work. The idea about pointing to the dead is explored in, among others, Avery Gordon in Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. There, she sees the ghost as a cultural-political figure who can be used to recall the violent past. But according to Gordon, the work of resistance does not stop at making visible post-colonial, anti-fascist or queer experiences of history, but it is what has been lost to us, that which “haunts us” that must be allowed to speak. The biggest defeat, according to Gordon, is not what happened but “what never happened”. And by giving voice to the ghosts, we can make room for both lamentations about the past and fantasies and notions about what could have become and what can become.

Maybe the Deep Space version of Valle de los Caídos can enable both counter memories and a platform for ghosts? In terms of the identification and return of the remains, Deep Space presents a solution that circumvents the physical problems of the site by expanding the physical spaces with the help of artificial intelligence and virtual worlds. In this way, the crypts and the remains can stay, but the material and architecture are enriched with information and experiences that remember and tell about those who are buried there. Deep Space argues that the advantage of such a hybrid architecture that mixes physical and digital spatiality is that the monuments can be filled with meaning without necessarily interfering with the materials.

The management of the Valle de los Caídos is of paramount importance to the Spaniards as the legacy of the dictatorship continues to have an impact on people’s lives. In the 2018 referendum, the right-wing populist party Vox doubled its support in the population. At the same time, loud protests were held against the excavation of Franco’s grave. With 15 percent of the seats in parliament, Vox allows Spain to join several other European countries where hyper-nationalist parties have been given heavy positions of government. At the same time, there is concern about the future of the digital society and who in the economic system will be assisted by that technological innovation. Hybrid Space Lab proposes a digital architecture as a tool to think carefully about the past and to make memorial sites an arena for the fallen rather than for the dictators.

Editorial Team

Hjärnkontor

With this number in your hand, you hold a piece of nostalgia. But also something that stands outside the nostalgic. That is our hope.

Hjärnstorm entered this project with the ambition to call in and expand, criticize, and affirm. Is it possible to perform something like this with a concept that is not only broad and popular but also elusive and personal? And which can also be used as an insult?

We started by consulting the Swedish Academy:

– What is nostalgia, actually?

– Nostalgia is melancholy but pleasure-filled, longing for home or back to something lost (especially about the longing for our childhood and youth environments).

– Could it be something more?

– Nostalgia is (melancholy) the longing for home, the pining for.

A little later, during a break with Trocadero, strong tea, pink cookies, and cheesecakes, we began to think about whether the Swedish Academy can really know everything about what nostalgia is and could be. This was at the beginning of our work with this issue and how far we still had ahead of us, so little we knew. We had not yet gotten in touch with the Nostalgic Academy, with the help of which the material in this thematic issue has been able to take different and sometimes unpredictable directions.

Of course, we have disagreed, with each other and with the experts, about the limits and content of nostalgia, and of course, we still do not really agree. Is nostalgia okay or not?

At some point in the future, we may look back on this time in a shimmer.

Editorial Staff, Hjärnstorm, the Swedish independent journal of art, literature, philosophy

related PROJECTS

related PRESS