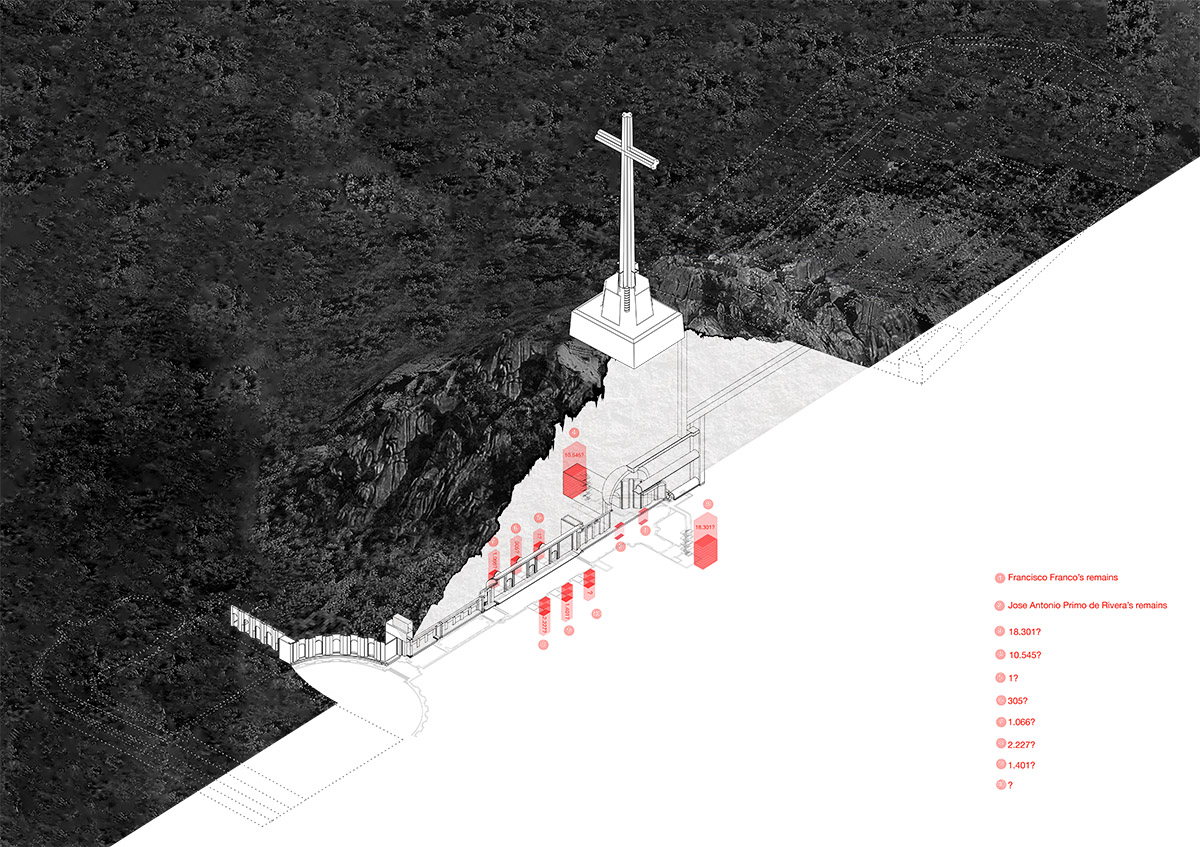

The Valley of the Fallen without Franco: the fate of the other 33,847 dead.

This is the title of the article by journalist Sílvia Marimom in the Catalan Newspaper ARA on the future of the Valle de los Caídos and Deep Space.

Article The Valley of the Fallen without Franco: the fate of the other 33,847 dead, Sílvia Marimom @ Catalan Newspaper ARA, Barcelona, 23 November 2019

What can the

Valle

de los

Caídos

be

tomorrow?

Franco’s final burial site is Madrid’s public cemetery of Pardo-Mingorrubio, where Francoist presidents Luis Carrero Blanco and Carlos Arias Navarro are also buried as well as several ministers of the dictatorship and the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. But in the Valle de los Caídos, Primo de Rivera will still remain alongside the stones that demonstrate what the Franco’s regime stood for as well as another 33,847 more remains. What can the Valle de los Caídos be tomorrow? How can you guarantee that Mingorrubio does not become a fascist pilgrimage site? And can the Valley be an opportunity to generate a new consensus on how Spain faces its memory?

In 1958, on Spanish roads military trucks loaded with wooden boxes that carried the remains of soldiers from all sides of the entire country to the Valley of the Fallen began to circulate. The last remains that entered the fascist monument, in 1983, were of Juan Álvarez de Sisternes, mayor of Vilafranca del Penedès. In most cases the remains were removed from mass graves without the permission of the relatives and, for years, there has been quite some litigation because of the relatives wanting to recover them. It is the Benedictine community that is in custody of these totally invisible remains. “We do not yet know in what condition the crypts are. In some places you have mountains of bones and in others the coffins are still intact. The identity of these dead was removed and must be recovered,” explains the historian Queralt Solé, author of “Los muertos clandestinos” (Editorial Afers).

The anthropologist of the CSIC Francisco Ferrándiz, one of the experts who wrote the report on the Valley of the Fallen in 2011, believes that it should become a public cemetery under the custody of the state: “A unique protocol should be established to respond to all exhumation requests. The state should respond to the demands of families, and they should not fight alone in court.”

On April 1, 1940, a decree was published in the Spanish state’s official gazette BOE describing in detail what the Valley of the Fallen was to be. It was very clear that the Valley had to pay tribute to those who had won the war, the winners, those considered “fallen for God and for Spain.” “You can not continue to use public space to apologize for the Franco regime, it is an offense to the victims,” says the law professor Alfons Aragoneses. A law decree of 1957 specified that the Benedictine Order had to guard the monument and gave the Fundación de la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos full legal responsibility to administer its assets. For Ferrándiz, it is a priority to change the legal status of the monument: “It can not continue to be governed by decrees of the Franco regime. You have to go deep into it, transform it radically, change the profile of the visitors and turn it into a place of critical memory. This can be done with the help of new technologies, the pixels must embrace the monument”. Connected to this idea, last summer, Deep Space was launched, an international think tank consisting of artists, archaeologists, scientists, psychologists and historians whose purpose is to rethink the future of the Valley.

“Now we see what Franco wanted us to see. With Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality we could show everything he wanted to hide,” explains the architect Elizabeth Sikiaridi, one of the heads of Deep Space. Sikiaridi, who also heads Hybrid Space Lab, based in Berlin, argues that with the help of new technologies many things that have disappeared can be shown: from the field barracks where the prisoners of war who built the monument lived to the victims of the Franco regime. In addition, they can also function as tools to overcome the trauma. “Digital tools can be used to debate, to discuss, as a therapy, especially among young people,” says the architect. Sikiaridi also mentions examples of such new tools with which some Holocaust museums work: “Conversations with Holocaust survivors and witnesses have the strongest impact. Since there will be few survivors, digital tools enable the visitors to ask them questions and to have conversations with them even if they are absent.”

Catholic symbols are another debate topic. “It is a forced reconciliation. The monumental Cross is a constant reminiscence of what Francoism was,” says Solé. The historian and director of the European Memoirs Observatory, Jordi Guixé, also believes that the space should be desacralized and, if there are any symbols left, these should be explained: “In Germany they did this with the castle of Wewelsburg.” In this German town there is a large German soldiers’ cemetery, some almost non-existent remains of a prisoner’s camp and the medieval castle that hosted Himmler’s SS headquarters. As the Nazi leader was fond of esoteric issues, they kept such symbols and objects there. The most controversial was the Black Sun. “This symbol is currently exhibited, and it is used as a space for reflection,” says Guixé.

The monks of the Valley of the Fallen have fought strongly so that the dictator – whom they call Him – would stay at the Valley. “The monks can not stay there because they have become themselves the custodians of the dictator. They have fought until the last moment,” says Ferrándiz. The dictator’s network has also kept a connection to the state, but the Spanish government has not made the new burial into a state funeral. Will now Mingorrubio become a kind of Predappio, the town where Mussolini is buried? There the cemetery is also public, but the crypt of the Italian dictator is private, while that of Franco and his wife will be paid by public money. Predappio has become a destination for nostalgics of the Italian fascism, and there are many shops that sell Duce souvenirs, including Benito’s ice creams. Those responsible for this lucrative business of Italian fascist nostalgia rebelled when there was talk about the possibility of closing Mussolini’s crypt.

“It would have to clearly signalize and explain who Franco was, and what the dictatorship was,” says Guixé. In any case, it should not be a comfortable space for those who swallow it”. Aragoneses argues that the state should go further and not use the memory for political purposes: “There is talk of pinkwashing, a term to explain how with the defense of gays and lesbians and the connected propaganda some countries try to hide human rights violations. We should not do memory washing.”

related PROJECTS

related PRESS