The Valley of the Fallen is a large memorial erected near Madrid in the mountain range of the Sierra de Guadarrama on the initiative of the dictator Francisco Franco.

The Valley of the Fallen is a large memorial erected near Madrid in the mountain range of the Sierra de Guadarrama on the initiative of the dictator Francisco Franco. It is dedicated to the fallen of the Spanish Civil War. Within the scope of the project “Deep Space” it is proposed to transform the monument by digital means.

“Deep Space” is a long-term research project that focuses on memory spaces, memory politics and controversial memorial sites in the digital age. It researches methods and ways of dealing with disputed places. Creative processes and digital tools play an essential role. Deep Space is a project by Hybrid Space Lab.

The Valley of the Fallen (Valle de los Caídos) is one of the most controversial memorial sites in the world. Its 152 meter high cross can be seen up to a distance of 30 kilometers. The “Basilica”, a crypt 262 meters long and 42 meters high, was knocked out of a granite rock. It runs on a large forecourt, which provides a very scenic view of the landscape.

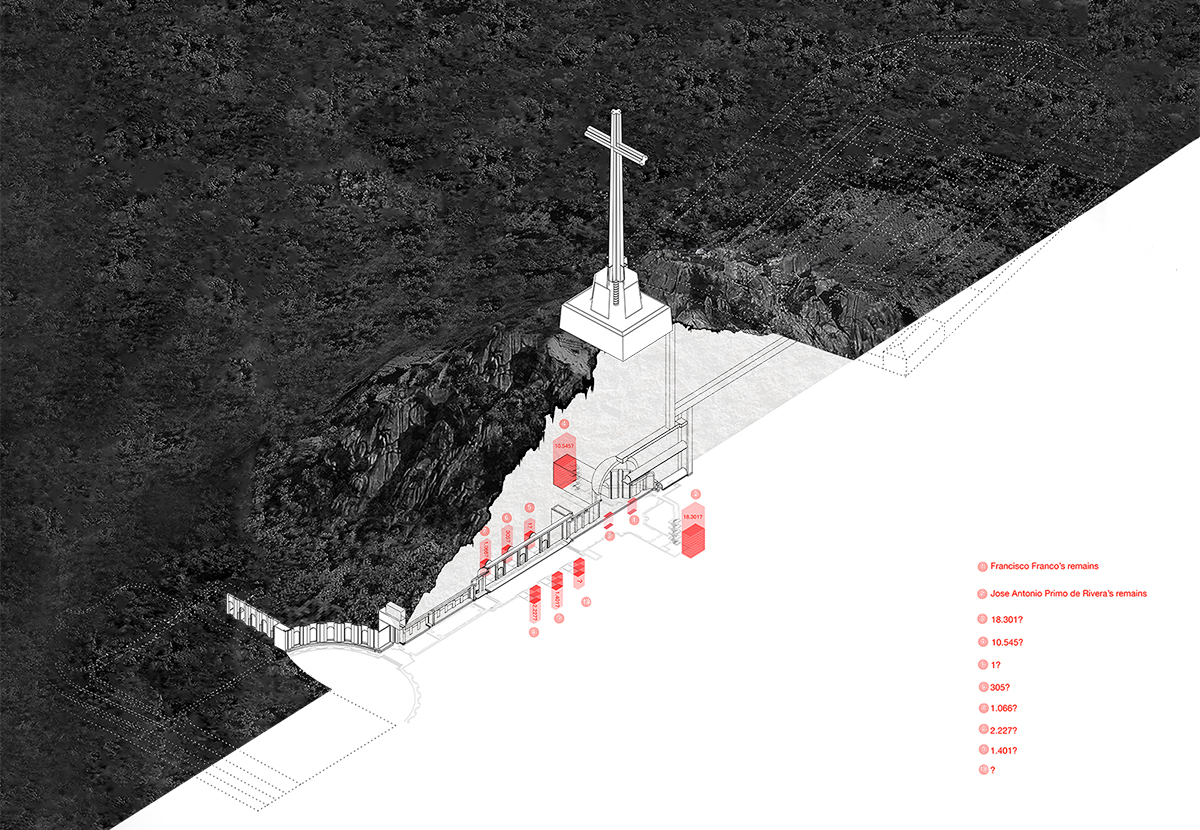

The complex was built between 1940 and 1959, partly in forced labor of republican prisoners. Along with the remains of 33,000 dead of both hostile camps of conflict (brought from mass graves all over the country), the grave site of Franco is placed at the most prominent point of the basilica – right next to the Falange leader José Antonio Primo de Rivera.

The memorial site of the Valley of the Fallen is reached via roads and paths that are laid out in a kind of pilgrim landscape and fit into a broad, through-composed landscape design – on a site that still contains remnants of the accommodations for prisoners of war.

In recent years, Spanish politics and society have intensified public discourse about the changes that should be made in the Valley of the Fallen. This was confirmed by the decision taken by the Spanish Government in 2018 to exhume the remains of Franco. However, this alone would create a cenotaph if the entire memorial is otherwise untouched: an empty tomb for the dictator.

Therefore, it is urgent to change the narrative of this place. All the more, bearing in mind that it is still a busy monument: Every morning at eleven o’clock, the Benedictine monks who manage the site celebrate Mass at the tomb of Franco (and in his honor); The place is also a place of pilgrimage for today’s Franco nostalgics of the extreme right.

In spite of the public discourse, in the face of controversy and historical wounds, reconciliation in the sense of collective remembrance seems a long way off. So far, there has been no creative-artistic approach that has explored new ways and ways of transforming and reinterpreting the Valle de los Caídos.

This is where the project “Deep Space” comes in. In October 2018, we (Hybrid Space Lab) organized the workshop “Deep Space: Re-signifying Valle de los Caídos” in Madrid, in which we explored how the Franconian monument could be redesigned and redefined. The international and interdisciplinary workshop explored the potential of creative formats and methods as well as digital means in dealing with historical heritage. Ideas and processes were sought that could help overcome conflicts and transform the symbolic power of the place, with a focus on artistic, architectural, landscaping and media approaches.

The workshop brought together Spanish and international experts such as architects, landscapers, designers, artists and curators with historians, cultural scientists, art historians, political scientists, ethnologists, forensic archaeologists, psychologists and psychiatrists.

The workshop drew its potential from an external perspective to bring a new perspective to a seemingly irresolvable conflict situation, as it has proved helpful in other cases. For example, the American historian Robert Paxton, in his research on Vichy France, has shown how the French Pétain government pursued its own authoritarian and racist policy (based entirely on Hitler’s ideological line).

Films can also filter events so that the viewer gains distance. The more than nine-hour documentary “Shoa” by French journalist and filmmaker Claude Lanzmann in 1985 marked the beginning of the debate over the crimes committed at the various locations of the Holocaust in Poland. In Poland, however, he was understood as a charge of complicity in the National Socialist genocide. Commenting on the Dutch colonial history in Indonesia, the Swiss-Dutch historian Remy Limpach remarkably pointed out the dreadfulness and scope of the Dutch war crimes, undermining in this way the official historical account of colonialism in the Netherlands.

With such groundbreaking historical precedents, the workshop showed that local history can be painful, and that a variety of perspectives, with the participation of local and external views, can contribute to an inclusive outcome.

In addition to the general public debate, which focuses on the question of the most suitable location for the remains of Francisco Franco and Jose Antonio Primo the Rivera, the workshop focused on the largely anonymous victims and the convicts who carry the boulders had.

The information, which is available in print, online and at the place of the memorial, says nothing about the fate of prisoners of war who were forced to work on this structure, let alone their families who lived in nearby barracks in the valley. There is also no mention of the fact that mortal remains of fallen Republicans from mass graves from all over the country were transferred to the Valley of the Fallen without their families knowing. This is extremely problematic because any process of reconciliation must be preceded by full recognition of the facts. The documentation and dissemination of the architectural history of the Valle de los Caídos would make it a testimony of totalitarianism and a tangible proof of its authoritarian character, ie a memorial.

An approach that incorporates the voices of the Republican side, the victim, corresponds to the current search for alternative narratives and historiographies. It follows the general demand for an inclusive historical narrative and corresponds to the current paradigm shift in historiography, which seeks to include both voices of national liberation in the context of postcolonial processes and enriching perspectives on gender studies and LGBTI.

As digital tools enable decentralized and co-creative bottom-up initiatives to democratize information processing, we are experiencing a veritable explosion of interest in remembering and its multi-faceted dimensions. The power relations inherent in the writing of the collective memory become weaker and blurred. The digital transformation now makes it possible to perceive a variety of different voices, which can be adapted to alternative narratives. This implies that the elaboration of memory transforms into an interwoven hybrid – physical and digital – practice whose actors are increasingly heterogeneous.

The workshop focused on the possibilities of using digital tools to bundle information about this monument and support its transformation without physical intervention. (1) Such hybrid technological tools that connect the physical and the digital can help transform a monument without physically interfering. With Virtual and Augmented Reality, for example, the digital environment of the Valle de los Caídos could be extended to include the archaeological remains of the barracks in which the forced laborers had to live during the construction of the monument.

Other tools could include databases and archives that are networked for academic or public use, sound recordings of important contemporary witnesses, and interactive educational platforms. It could support such a discourse, from the proposals for the longer-term, then physical transformation of the place emerge. Interdisciplinary and collaborative bottom-up contributions dedicated to the monstrous history of the monument could find their place in an archive and become accessible. This would promote dialogue and, with a polyphone network of democratically voiced voices, compensate for the place’s totalitarian narrative. The handling of cultural heritage and the construction of memories could be imagined in larger time periods and other spatial references.

The proposals developed in the workshop will now be further explored and examined in discussions with the responsible persons and scientists, if and how an implementation is possible. That will not be easy, because such an approach also has opponents who can also network and intervene well via digital media. But we insist that the strategy of transforming the monument can be persuaded without changing it physically. If the invisible layers of the place were to be experienced, this could pave the way from recognition to reconciliation. Also in the further treatment the view from the outside should be given a significant role, in order to the

Conflict-rich historical-political controversy to break through and new perspectives for

to open the future of conflict-laden monuments. Let us not forget how much the Federal Republic of Germany has benefited from these views from outside.

(1) fall under the digital technologies

– augmented reality (the physical reality is enriched with the help of computer generated perceptible information)

– Virtual Reality (an interactive computer-generated experience that takes place in a simulated environment)

Mixed or hybrid reality (a combination of real and virtual worlds to create new environments and visualizations in which physical and digital elements coexist and interact) and the

– augmented virtuality (an interactive experience of a real-world environment in which the objects contained therein are enriched by means of computer-generated perception information)

related PROJECTS

related PRESS