The way people communicate and connect around the world today, is being radically redefined by digitalization.

With the acceleration of digitization as one of the most obvious consequences of the pandemic, the use of digital tools is experiencing an unprecedented rise among arts and cultural institutions and practices.

Publication hybrid @ tanz Yearbook 2022, Germany, 19 August 2022

Exploring the future of artistic-cultural spaces requires looking at physical spaces together with digital media networks. Polyphonic hybrid cultures are anchored and embedded in physical spaces, while at the same time they are increasingly distributed, formed, disseminated, shaped, and negotiated across digital networks. With the ongoing merging of the physical and the digital, new scenarios and new forms of experience and participation in artistic-cultural life emerge.

As avoiding and reducing physical mobility is crucial to the shrinking of the ecological footprint and therefore to sustainability, we are prompted to explore meaningful ways of combining physical proximity with digitally overcome distances. This urges us to filter out the best of both worlds, the physical and the medial and to bring together and combine these dimensions intelligently and effectively to create memorable experiences, to enable creative interactions, and to support outreach.

Integrating music, light events (Polytopes) and architecture, the famous Greek and French music composer, media artist, architect and engineer Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001, with 2022 marking the centenary from his birth) developed the “Poetics of the Electronic Age”, in his own words, incorporating the new, universal, electronic tools of the computer in his artistic oeuvre. Xenakis argued for the development of a general discipline of form, a “General Morphology”, an effort that would match his universal thinking and his transdisciplinary practice.

Xenakis deployed the computer to control and (de-)synchronise the overlaps between musical and visual events (Polytopes) and integrated the computer in his creative process to help generate and control his complex compositions. To achieve this, in the late 1960s Xenakis started developing a custom-made computer. This digital instrument was especially striking, as it consisted of a music-computer relying on a traditional architect’s drawing board as interface, directly translating graphical information into music and sound.

Xenakis’ approach to the digital instrument’s interface is especially interesting. His music-computer is not merely based on informational programming. With physical movement needed to manoeuvre the drawing board, Xenakis’ musical interface responded – and thus corresponded – to bodily intuition. Even if mathematical information is the actual bridge running between the two expressions – the visual graphical one and the acoustic one of music and sound – the bodily embedment of emotions and consciousness anchors creativity in somatic, physical space.

Nevertheless, the digital did provide the connecting link, as it bridged visual form to acoustic form by means of mathematical information. This reflected Xenakis holistic artistic approach and materialisations across very different media and dimensions, in sound, light, time, and space.

In his pioneering work, Xenakis’ all-round creativity was supported by his computational instrument and he captured a main feature of this contemporary ubiquitous and universal tool in its quality as a radical merger. Today, creative production in its most varied forms of expressions – whether music, visual art, architecture, video, etc. – is supported by a single tool, the computer. This universal instrument provides a bridge which connects such very different creative fields.

This accelerates and stands in continuity with the ongoing trend of the merging of artistic fields. Since the late 1960s, contemporary art practices have transcended the boundaries of traditional artistic media, for example, of sculpture and painting, thereby entering the ‘post-medium condition’ described by Rosalind Krauss (2000). Painting and sculpture come together with video, film, performance, theatre, dance, music and sound, interactive media, and digital art and various media fuse within a single artistic project. Medium-specificity is in no way determinative of artistic production – the art fields merge.

Today, we are experiencing hybridizations of artistic and cultural practices in several dimensions. Different media come together in one artistic oeuvre. Artists and cultural practitioners work in transdisciplinary research. At the same time, they integrate virtual tools and spaces into their work. Hybridity has pervaded culture by blurring its distinctions, methods and roles, fading the lines between disciplines, approaches, cultural creators and recipients. The emergence of such hybrid creative practices demands for a new – a hybrid – approach.

This calls for transdisciplinary spaces of exchange, such as the INbetweenSTITUTE initiated by Hybrid Space Lab, bridging between the different art and culture institutions, providing a transdisciplinary platform for cultural institutes, activists, laypeople and audiences to co-create cultural innovation. INbetweenSTITUTE is conceived as an un-disciplinary experience where cultural innovation occurs and unfolds. Involving artist, creatives, cultural professionals from very different fields and bringing them together with scientists and experts, activists, entrepreneurs, and decision makers in transdisciplinary international meetings and workshops, the program fosters exchange and mutual enrichment.

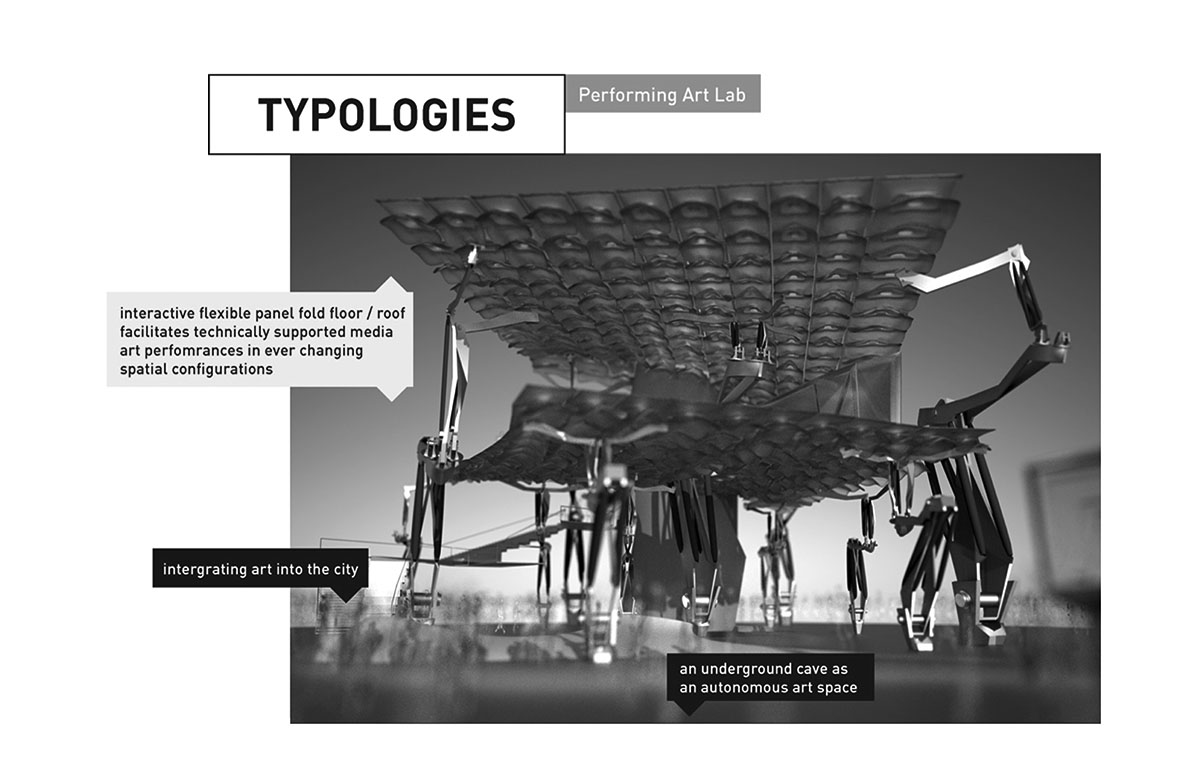

Addressing the challenge of the spaces hosting transdisciplinary artistic processes, Hybrid Space Lab also developed typologies for hybrid artistic practices such as mergers of performing and visual arts. In a 2014 assignment for re-developing the China’s art and cultural hub “798” in Beijing that we will discuss more thoroughly later, we developed a typological study for a performing arts centre as a hybrid art institution for post-media art. Whilst the basement hosts a “Cave” functioning as a production and presentation space cut off from the outside, the pedestrian level is open to public urban space and supports the structure of an interactive dance floor that responds and adapts to changing requirements and to performers. This model of an interactive responsive hybrid space for transdisciplinary art practices, opening to its urban surroundings, also allows for an involvement of the public and city users in artistic-cultural co-creation.

Next to the confluence of artistic fields merging in hybrid artistic production, we are simultaneously experiencing a hybridization as a fusion of art and culture creators and consumers, as artistic-cultural co-creation. As digitization enables the transition from centralized to interactive, decentralized social networks, this makes possible to integrate complex dynamic network systems with processionary structures in the artistic practices. In this context, the latter are integral elements, embedding artistic expression into the networks of social relationships.

Digital tools and networks support these processes of polyphonic artistic co-creation that are anchored and embedded in physical spaces and at the same time simultaneously increasingly shaped and negotiated in trans-local media networks.

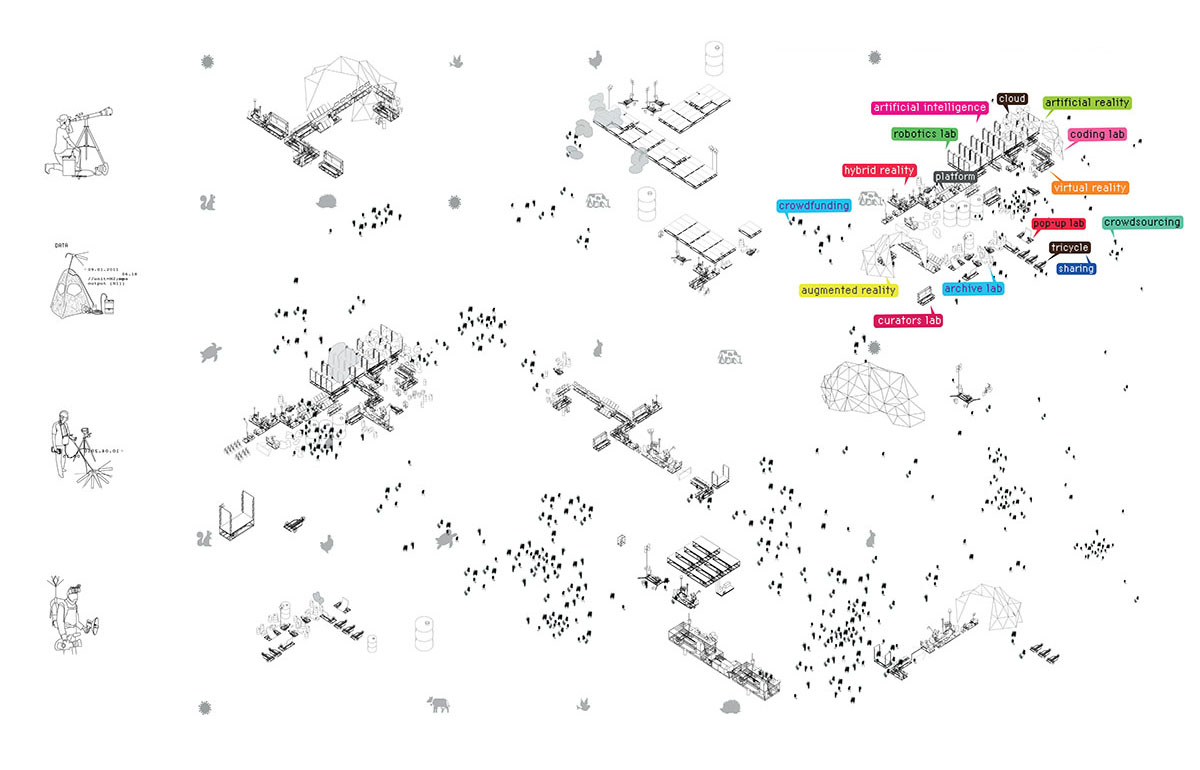

This challenges the way cultural institutions should respond to this with new hybrid (combined physical and digital) spaces and formats. What are possible formats that connect the (private) artists’ and performers’ spaces with the public spaces of the co-creating audience? How could infrastructures and platforms support online and on-site audiences, promoting artistic co-creation in hybrid space? To address this Hybrid Space Lab developed, in the context of the aforementioned project for the Beijing Art Quarter 798, models of a hybrid infrastructure for combined on-site and online co-creation and involvement of the public.

For years, Beijing’s 798 Creative Zone was the most important Chinese art district, with museums, galleries and studios in an old factory area. Due to its success, the 798 Art District became more and more a tourist destination, which increasingly undermined its exclusive image. In 2014, we were invited to, to propose a new branding and museum facilities for the district. However, we invited Beijing-based decision makers not to think in terms of brands, but in terms of processes and communication spaces and proposed a process-oriented strategy to strengthen creative networks and anchor them in the city fabric.

We developed models for spaces between the private space of artistic creative work (atelier, studios) and the public space of the audience, like public showrooms, museums, galleries, theatres or concert halls, as an infrastructure, that enables and supports the participation and involvement of the public.

The project also fostered a hybrid modular and mobile system, that can penetrate the city in order to involve citizens in active participation. This model of a hybrid modular mobile system was further developed, e.g., within the framework of a Creative Europe project, for co-creative workshops in different European cities which take place in public spaces, to support an active online participation of international artists and experts. Such a modular mobile infrastructure (e.g. on tricycles as modular self-built expandable cargo-bikes) is a sustainable sharing model. With its Circular Economy concept, it is relevant also for smaller decentralized cultural institutions, supporting hybrid (combined online and on-site) co-creation processes.

Drawing on a long-standing experience with hybrid spaces and formats, Hybrid Space Lab’s has been experimenting and testing hybrid co-creative events and workshops such as “The Future is not Digital. Hybrid is the Future!” for the German Federal Cultural Foundation in October 2021. The five-hour workshop, held at Hybrid Space Lab’s premises in Berlin, allowed to experiment with co-creative processes deploying the tools of a hybrid design studio. Twenty on-site participants and thirty-five online participants attended the hybrid workshop, interacting as well as reflecting on the potential of the new format they were enabling and witnessing.

Issues essential to hybrid (combined online and onsite) creative formats in the interplay of the physical and the digital, such as camera direction, performative qualities, visual intelligence, and the many dimensions of sound and space were informed by the transdisciplinary expertise of the participants. With workshop contributors coming from very different artistic and cultural fields, the communal hybrid spaces were simultaneously tested from the very different perspectives.

In these upcoming hybrid (combined physical and digital) spaces also the bodies are ‘hybridized’. Immersive imaging technologies that use computer-generated imagery and sound integrate digitally re-created human (or more-than-human) beings as virtual actors.

For example, the Volucap Studio in Potsdam-Babelsberg – a joint project by among others scientists from the Berlin-based Frauenhofer Heinrich-Hertz-Institute for Telecommunications together with technology companies, the film and television production company UFA and Studio Babelsberg -develops ‘libraries’ of digital actors for the special effects industry.

At the Volucap Studio, actors are recorded from all sides and their lifelike avatars are integrated in virtual environments with the help of “3D Human Body Reconstruction” technologies. 32 HD cameras installed in the studio’s rotunda simultaneously record all actors’ motions, facial expressions – including up to such details as iris movements – as well as every drapery folds of the actors’ garments. Furthermore, the sophisticated lighting system in the rotunda can project different light situations on the actors – from warm fireplace light to police blue light. The data of the actors’ lifelike avatars are then further processed in order to integrate the action in virtual environments as well as in recordings of physical spaces.

Also, bodies are expanded and ‘augmented’ in digital (networked) spaces, for example, with real actors and dancers performing in motion capture suits, animated in real-time, spontaneously interacting with virtual environments and with their distributed online audiences. A 2021 production of the Royal Shakespeare Company portraying Puck of “Midsummer Night’s Dream” on his journey through a magical woodland, was live-streamed to audiences that followed virtual avatars with the performers’ bodily movements and voices in a virtual world. The production was the result of a multi-year research and development collaboration with the London-based creative studio Marshmallow Laser Feast, aiming at developing innovative methods of audience engagement with the help of digital tools.

The surrounding forest’s setting was a pre-designed virtual environment, integrating also imagery of plants mentioned in Shakespeare’s theatre piece that would be found in English forests at the time the play was written. Motion capture cameras recorded the performers’ movements and expressions while large LED screens surrounding them supported them in understanding where their avatar was in the virtual woodland – whether close to the roots, on the branches or flying over the treetops.

But it was a real-time live setting, the actors performing in facial rigs and motion capture suits, animated in real-time as the play was being acted out and live-streamed to the audience. The actors had multiple possibilities and ways for interacting with each other, with digitally animated rocks, roots and branches as well as use their movements to influence the play’s music score, as all the different instruments had been pre-recorded (by London’s Philharmonia Orchestra) separately.

Also, the theatre play’s audience could actively participate – as the virtual forest’s fireflies that could be controlled online from the comfort of their living room via simple interfaces such as a mouse, a trackpad or a touchscreen and thus interact with the performers – as fireflies, guiding Puck by lighting up the virtual midsummer forest.

This real-time performing and interaction allowed therefore for spontaneity, improvisation and unanticipated accidents, with each performance being unique, reflecting the authenticity and impromptu of in-theatre plays.

Such active participation of the audience engaging across distances relies on the digital networks’ inherent quality of enabling the transition from centralized one-to-many sender-receiver-models to interactive, decentralized many-to-many co-creative networks.

The digital networked space with its flows of data was poetically addressed and translated in the 1995 “Ping Body” performance by the artist and hybridization pioneer Stelarc, allowing his body to be controlled remotely via Internet. A dispersed audience in different locations – in Amsterdam, Helsinki and Paris – tele-accessed, viewed and actuated Stelarc’s body via a “computer-interfaced muscle-stimulation system”. The collective Internet activity activated the body’s proprioception and musculature to unfold an ‘unusual’ dance. Parallelly, with a robotic “Third Hand” he could control, Stelarc uploaded images of his performance, watched by a global audience.

Stelarc experimented with extending the human – actually his own – body, enhancing its capacities through human-machine interfaces, prosthetics and robotics. Today, similar practices are becoming state of the arts in medicine, with for example, hearing implants placed (by operation) inside or on the skull. Raising cultural, political, and ethical questions, Elon Musk’s brain-computer interface firm “Neuralink” claims it enabled a monkey to play a video game by brain signals sent wirelessly via an implanted device.

Brain-computer interface research aims at helping people with physical disabilities such as total or partial paralysis, allowing them to control digital devices remotely. Also, assistive technologies to help a person overcome an injury or to enhance their biological capacities are being developed in the form of prostheses and of external frames supporting the body as exoskeletons that can be powered by electric motors giving extra movement, strength and endurance. Pushing these developments further, University of Melbourne researchers are testing – first on sheep and now on paralysis patients – devices capable of controlling the exoskeletons using the human mind via brain-computer interfaces.

The interiorization of digital networked systems – in the body – corresponds to the exteriorization of consciousness – in media spaces. As a result, our identities are performed and formed in digital networked spaces. Social media enable constructions of multiple self-images; our physically embedded cultures are shaped and negotiated across trans-local media networks.

Today’s networked digital culture is trickling down to our physical existences, and to how we model our physical presence. In today’s selfies-culture, our faces stand for our identities in networked spaces such as Instagram. Digital representation affects our physical presence, too, with, for example, teen-age girls aiming to emulate Kim Kardashian – following a phenomenon that could be described as “Kim Kardashianisation” – with the help of makeup dedicated to selfie, arm-length photographic representation in order to comply to Instagram aesthetic canons.

The dancer’s studio mirror-wall with its function as a control tool for the disciplining of the dancer’s body, mirrors and resonates the 17th century Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles as a movement control device for the nobility’s performance. Today, analogous phenomena – albeit supported by radically different technology for mutual surveillance and monitoring – may be observed across our everyday experience. A variety of social media platforms and formats ensure that people are constantly reminded of what is good social-media shape, appearance and form, as well as aesthetic etiquette. For instance, on the Tik-Tok networked, diffused landscape that with its special camera standing point monitors, disciplines and reproduces specific social-media-proof and appropriate bodily movements and expressions.

As an upshot of these considerations and observations, the interplay of physical spaces and digital networks warrants new ways to chart explorations of human and other-than-human movement into the Hybrid. This radically challenges the divide between performers, performance, and audience. And also demands a radical rethinking of how our physical and digital presence inhabit and, by inhabiting, design and define, virtual, non-virtual and hybrid spaces.

related PROJECTS

related NEWS